Every large institution faces the same quiet frustration: outdated profiles, incomplete project descriptions, missing expertise, stale research information. The organization knows this information exists - it's happening in real time across departments - but its digital representation lags weeks, months, sometimes years behind reality.

The standard response is to treat this as a compliance problem. Send reminders. Create policies. Mandate updates. Assign responsibilities. And yet the problem persists, because the diagnosis is wrong.

The information isn't stale because people are negligent. It's stale because the system is built from the wrong perspective.

The Institutional Perspective

Most information systems are designed from the institution's point of view. The organization needs accurate profiles. The organization needs current research information. The organization needs to showcase expertise. The organization needs comprehensive reporting.

All of this is true. But here's what gets missed: busy professionals - faculty members, researchers, department heads, project leads - do not wake up thinking about the organization's information needs. They think about their work, their collaborations, their deadlines, their careers.

When you ask someone to "update your profile in the institutional database," you're asking them to do work that serves the organization's needs, on the organization's timeline, with no clear benefit to them. The task competes with everything else demanding their attention, and it loses - not because people are uncooperative, but because the incentive isn't there.

Compliance-based approaches can work in narrow cases. Annual activity reports with clear deadlines and consequences get completed. Promotion packages that require specific documentation get assembled. But for ongoing, voluntary participation in the institution's digital presence - keeping profiles current, documenting projects, sharing expertise, contributing fresh content - compliance has sharp limits.

You can mandate data entry for administrative requirements. You cannot mandate genuine engagement with your institution's information ecosystem.

What Actually Motivates Participation

Individuals update information when it serves their interests: their career visibility, their professional network, their immediate collaborators, their department's needs. They maintain what they control and what benefits them directly.

A researcher keeps their personal website current because it serves their professional identity. A department head ensures their unit's site is accurate because it affects recruitment and reputation. A project lead documents their work because it matters to their collaborators and funding sources.

The pattern is consistent: people maintain information when they own it, when it serves their purposes, and when they see immediate value from the effort.

The challenge for institutions is that these individual motivations often appear to conflict with organizational needs. The researcher's personal website diverges from their institutional profile. The department's site becomes inconsistent with central systems. Information gets duplicated, fragmented, and desynchronized - not from malice or carelessness, but from rational individual behavior.

Organizations have traditionally responded by trying to centralize control: lock down personal sites, mandate use of central systems, restrict what individuals can manage independently. This creates coherence, but at a cost - the information becomes even more stale because you've removed the one reliable source of updates: people acting in their own interest.

The false choice seems to be: either accept fragmentation and inconsistency, or enforce centralization and accept staleness.

Building for Empowerment

The resolution isn't to choose between individual autonomy and institutional coherence. It's to align individual incentives with institutional needs through system architecture.

What if updating your information for your own purposes - managing your professional presence, showcasing your work, connecting with collaborators - automatically satisfied the institution's information needs? Not as an additional step, not as a separate obligation, but as a natural consequence of doing what already benefits you?

This requires a fundamental shift in how systems are built:

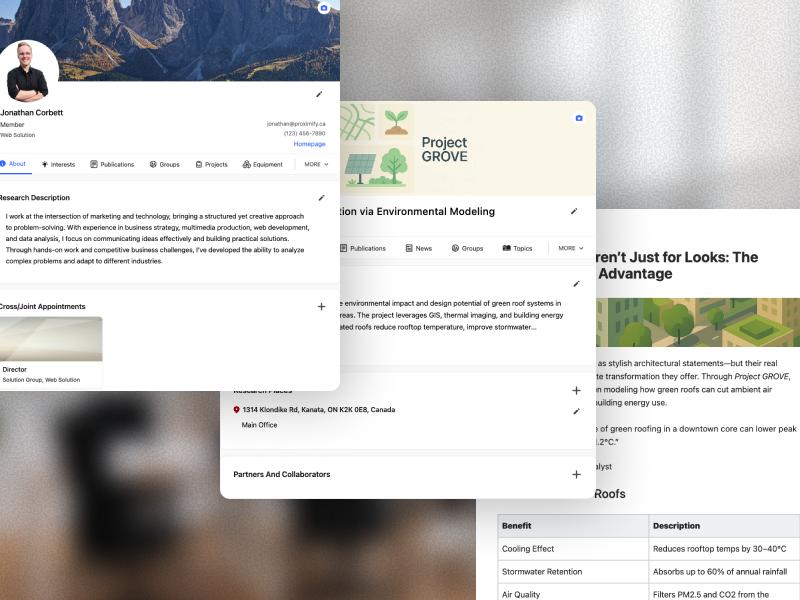

Give individuals tools that serve them first. Make it easy to create and manage their own digital presence - their profile, their projects, their expertise, their outputs. Not in service of institutional reporting, but because it serves their career visibility, their professional identity, their immediate needs.

Structure information once, use it everywhere. When someone updates their profile, that change should flow naturally through every context where it matters - the department site, the institutional directory, the expertise search, the annual report. Not through synchronization, but because all these views draw from the same underlying information.

Enable autonomy at every level. Individuals manage their profiles. Groups manage their projects. Departments can create and customize their sites. Not as separate, disconnected activities, but all working with the same coherent, shared information infrastructure.

Make creation as easy as maintenance. Writing an article, documenting a project, organizing an event - these should be straightforward activities that individuals and departments can do themselves. And when they create this content, it should automatically integrate with the broader institutional knowledge base.

The architectural principle is simple: eliminate the tension between individual empowerment and institutional coherence by building on a foundation where they're not in conflict.

The Reusability Principle

The key insight is about information reusability. Traditional systems create duplication: the same information must be entered multiple times, for multiple purposes, in multiple places. Every duplication creates maintenance burden, and that burden falls on people who have limited incentive to bear it.

When information is defined once and reused everywhere it's needed, the calculus changes completely:

A faculty member updates their research interests once, in their profile. That update automatically appears in the department's faculty directory, the institutional expertise search, the research group's member list, and any custom sites that reference their work. The individual does the work once, for their own benefit, and every downstream use case stays current automatically.

A department creates a project page - describing the work, linking team members, connecting to publications. That page serves the department's immediate needs (showcasing their work), but also feeds the institutional research directory, populates member profiles automatically, enables cross-departmental discovery, and provides data for reporting - without any additional entry.

This isn't about being clever with technology. It's about recognizing that people will maintain information they control for purposes they care about. The institution benefits not by extracting data from reluctant participants, but by providing infrastructure that amplifies what people are already motivated to do.

The Voluntary Engagement Problem

There's a deeper question here: how do you get people to participate in the institution's digital presence when participation is voluntary?

The answer isn't to make it less voluntary. It's to make participation valuable to the individuals themselves.

When your system gives someone real tools - the ability to manage their professional presence, create content that matters to them, build sites for their department, control what's visible and how it's presented - participation isn't a favor they're doing for the organization. It's something they want to do because it serves them.

The institution benefits from this engagement - current information, rich content, dynamic presence - but these emerge as byproducts of individual empowerment, not as the primary goal.

This is why the architecture matters so much. You can't bolt empowerment onto a system designed for compliance. The foundation has to be built around the principle that individuals are the source of information, and they'll maintain what they control for their own reasons. Institutional needs are satisfied when the system makes individual actions naturally serve organizational purposes.

Beyond the Central Database

The traditional model assumes a central database that everyone must feed: "Please update your information in the institutional system." The mental model is extraction - the organization needs to pull information from distributed sources into a central repository.

The alternative model assumes that information lives with the people and groups who create it, and the institution provides infrastructure that makes this information accessible, coherent, and reusable. The mental model is amplification - the organization provides tools that make individual efforts more valuable and more widely visible.

This isn't a subtle distinction. In the extraction model, you're asking people to do administrative work. In the amplification model, you're giving people tools that serve their interests while naturally serving institutional needs.

One model fights against individual incentives. The other aligns with them.

The Prestigious Domain

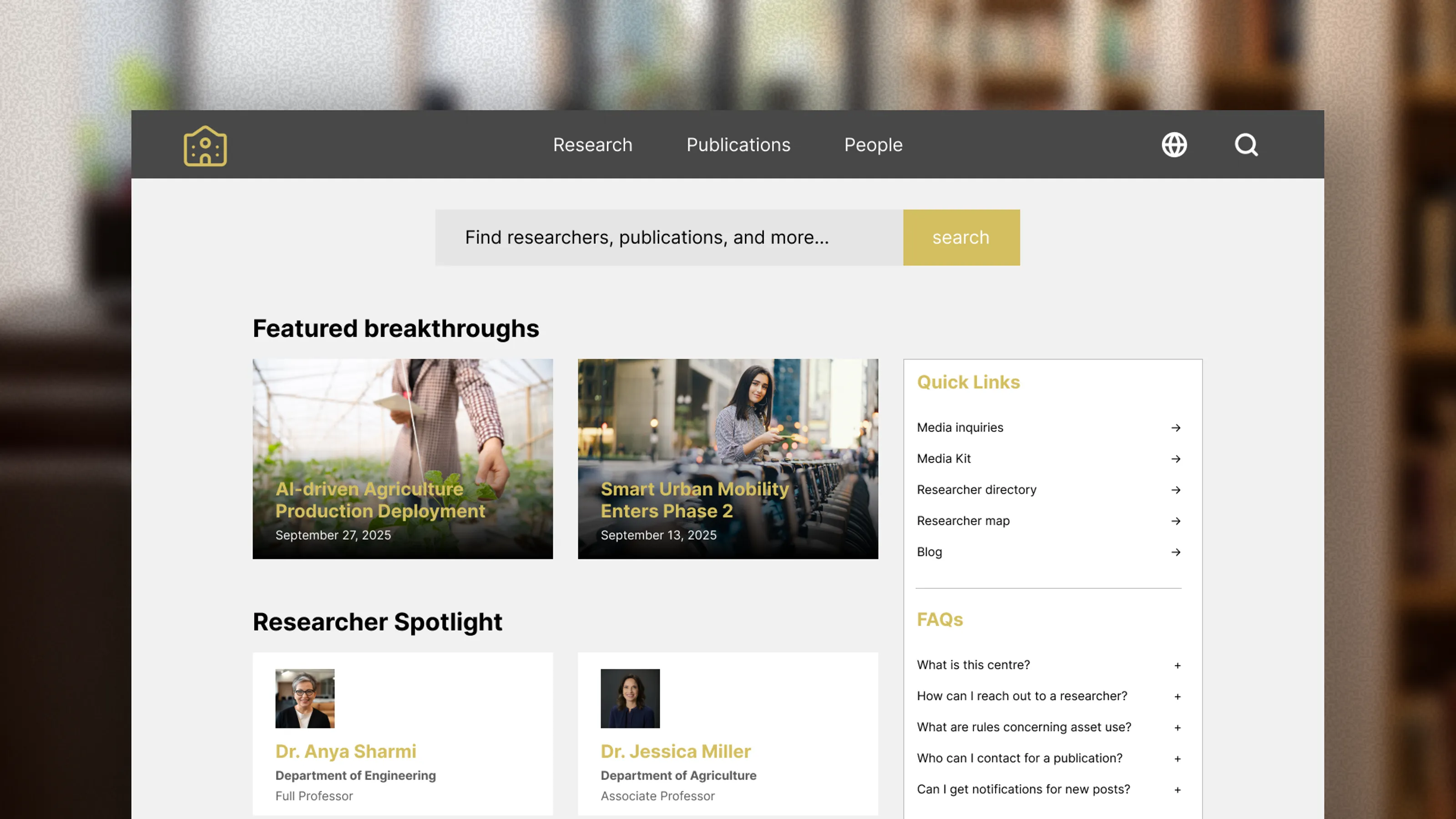

Of course, individuals do benefit from institutional affiliation. Being featured on a respected university or research center's domain carries weight. Having your work visible through institutional channels provides credibility and reach you might not achieve independently.

But this benefit only materializes if the institutional presence is actually good - current, comprehensive, well-maintained. If the institutional site is stale and the internal tools are burdensome, individuals rationally choose to invest their effort elsewhere. They build their own sites, maintain their own presence, and the institution loses both the information and the engagement.

The institutions that succeed in maintaining vibrant, current digital presence are the ones that recognize this dynamic: individuals will invest in the institutional presence when doing so is the best way to serve their own interests.

Make the tools good. Make participation valuable. Make individual effort automatically serve institutional needs through smart architecture rather than administrative overhead.

When you get this right, the question changes from "How do we make people update our database?" to "How do we support the content creation and presence management that people are already motivated to do?"

The Principle

The broader principle extends beyond information systems: design for alignment, not compliance.

When individual incentives and organizational needs appear to conflict, the problem usually isn't the people - it's the system design. Compliance-based approaches work against the grain of human motivation. Alignment-based approaches work with it.

This requires thinking carefully about who benefits from what actions, what people are already motivated to do, and how to build infrastructure that makes individually rational behavior collectively beneficial.

For institutional information systems, this means: build for the individual first. Give them tools that serve their needs, that they want to use, that make their work more visible and their management tasks easier. Structure information so that individual effort naturally propagates to institutional contexts. Eliminate duplication so that maintaining information once, for personal benefit, satisfies organizational needs automatically.

When you build this way, the stale information problem doesn't disappear because you've enforced better compliance. It disappears because you've eliminated the misalignment that created it in the first place.