Consider what your institution actually is: a network of people connected to projects, which produce outputs, which demonstrate expertise, which attracts funding, which enables more projects. A researcher belongs to a department, leads an initiative, collaborates with colleagues, publishes findings, speaks at conferences, mentors students. None of these facts exist in isolation - they form a web of relationships that defines your organization's identity and capabilities.

This isn't a metaphor. This is the actual structure of institutional knowledge. Your organization is, by its very nature, a knowledge graph.

Yet for decades, we've been managing this networked reality with tools designed for something entirely different.

The Publishing Paradigm

Most organizations rely on content management systems (platforms that power websites, intranets, and institutional databases) built around a specific model: publishing discrete pieces of content to the web. Articles. Pages. Posts. Documents. Each one independent, each one sitting in its place in a hierarchy, each one updated separately.

This model made perfect sense for its original context. Newspapers, magazines, and early websites had content that was genuinely discrete. An article about Policy X had no inherent connection to an article about Research Y. The filing cabinet metaphor worked because the content actually behaved like files.

But institutional information doesn't work this way. When Dr. Martinez leads a research project, that fact isn't a standalone piece of content. It's a relationship. It connects a person to an initiative. It implies expertise. It suggests collaborators. It produces outputs. It demonstrates capacity to funders. That single relationship cascades through dozens of contexts across your institution's digital presence.

The traditional approach forces you to treat this relationship as multiple independent pieces of content. Dr. Martinez's profile page mentions the project. The project page lists her as lead. The department page includes her in its research portfolio. The annual report cites the project in her section. Each instance is manually created, separately maintained, individually updated.

This isn't a limitation of specific platforms or vendors - it's the inevitable result of applying the publishing model to networked information.

What Gets Lost

When you force a network into a publishing paradigm, the costs compound in ways that extend far beyond stale websites:

The information becomes less true than it actually is. When Dr. Martinez moves departments, her profile updates, but her old department's page still lists her. The research project page is correct, but the archived news story isn't. The organization's actual knowledge - that Dr. Martinez is connected to this work - remains accurate, but its representation fractures into multiple versions, some current, some outdated, none authoritative.

Relationships that exist in reality become invisible in your systems. Your institution knows which researchers collaborate across departments, which projects share methodologies, which expertise clusters around which challenges. But if your platforms treat each profile and project as independent entries, these patterns remain locked in people's heads rather than surfaced as navigable, discoverable knowledge.

The cost of accuracy becomes prohibitive. Keeping information current isn't just a matter of diligence - it's structurally expensive. Each relationship that exists must be maintained in multiple places. Each change ripples through pages that may be managed by different people, in different systems, on different timelines. Organizations respond rationally: they accept inaccuracy as the price of operating at scale.

Autonomy and consistency become opposing forces. Departments need to manage their own content. Central administration needs brand consistency and accurate institution-wide views. Traditional platforms make these goals contradictory - either you centralize control and lose agility, or you distribute access and lose coherence.

The deepest cost is perhaps the most subtle: your digital presence becomes less intelligent than your organization actually is. The connections, the patterns, the relationships that define your institution's capabilities exist in reality but remain unexpressed in your systems.

Recognition, Not Solution

A knowledge graph isn't a technical feature or an architectural choice. It's recognition of what institutional information actually is.

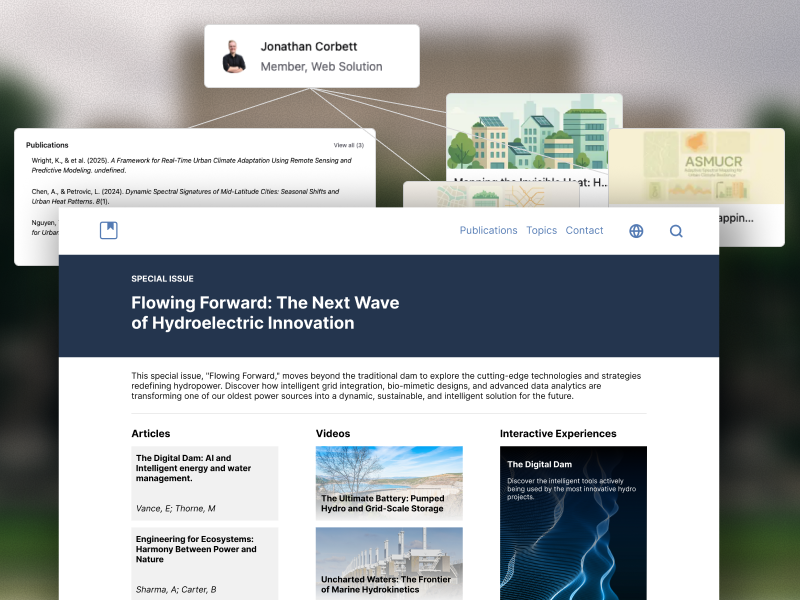

When you structure content around entities and relationships rather than pages and hierarchies, you're not imposing a new model - you're aligning your tools with reality. Dr. Martinez's connection to the research project is defined once, as a relationship. That relationship then expresses itself naturally in every context where it matters: her profile, the project page, the department's research portfolio, the searchable expertise directory, the automated annual report.

This isn't about making your existing systems "smarter" - it's about building on a foundation that matches the structure of your information.

The practical implications emerge naturally from this alignment:

Information becomes accurate by default rather than through sustained effort. When Dr. Martinez changes departments, the relationship changes once. Every page, every report, every context that draws on that relationship reflects the update automatically - not through synchronization, but because they're all expressions of the same underlying fact.

Patterns that exist in your organization become navigable in your systems. Which researchers work on similar challenges? Which projects share methodologies? Which departments collaborate most frequently? These aren't questions you need to answer by analyzing data - they're relationships that already exist, now expressed in a structure that makes them discoverable.

Autonomy and consistency stop being contradictory. Department members can create and manage content within their domain because the structure ensures that relationships remain coherent. Central administration maintains institution-wide accuracy not through control, but through a shared model that makes contradiction structurally difficult.

New capabilities emerge that weren't possible before. When your system understands that a person has expertise, leads projects, publishes research, and collaborates with colleagues - all as structured relationships rather than scattered text - you can surface insights that would otherwise require manual curation. Who are the emerging voices in this research area? Which cross-departmental collaborations are most productive? What expertise exists that isn't currently visible on the public website?

The Essential Foundation

The gap between traditional publishing-oriented platforms and institutional needs isn't narrowing - it's widening. Organizations generate more information, stakeholders expect more accuracy, and the complexity of relationships continues to grow. Trying to manage this with tools built for discrete publishing is like trying to capture a three-dimensional network with a two-dimensional canvas.

The question isn't whether to adopt knowledge graph principles - it's how long you can afford to operate with tools that don't recognize what your information actually is.

Modern institutions need systems that understand their information is relational by nature, that changes in one part of the network ripple naturally through connected contexts, that the same entity can appear in multiple places without fracturing into multiple versions, and that new patterns and insights emerge from the connections themselves rather than requiring manual curation.

This isn't about technology trends or features. It's about building on a foundation that acknowledges a fundamental truth: your institution is a knowledge graph. Your systems should be too.